Recent studies have shown that post-COVID stress disorder may be an emerging consequence of the global pandemic for physicians, other healthcare workers, patients who survived COVID infections, and the general public.

According to BioMedCentral.com, “Exposure to infectious disease epidemics results in a particular type of psychological trauma, which could be categorized into three groups.

The first is directly experiencing and suffering from the symptoms and traumatic treatment. For example, dyspnea, respiratory failure, gatism, alteration of conscious states, threatening of death, tracheotomy, etc. are major trauma of patients with severe COVID-19.

The second is witnessing of patients who suffer from, struggle against and die of the infectious disease, which has a direct impact on fellow patients, family members of patients, or people who directly provide aids and care for the patients.

The third is experiencing the realistic or unrealistic fear of infection, social isolation, exclusion, and stigmatization. This directly affects patients, family members, care and help providers, or even the general public.

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a rather high prevalence of mental health problems among survivors, victim families, medical professionals, and the general public after an epidemic of infectious disease, such as SARS, MERS, Ebola, flu, HIV/AIDS. While most of these mental health problems will fade out after the epidemic, symptoms of PTSD may last for a prolonged time and result in serious distress and disability.

A systematic review of psychological consequences of infectious disease outbreak (after 2003 SARS outbreak, the H1N1 outbreak in 2009, and occupational exposure to HIV) indicates that the average prevalence of PTSD among health professionals was approximately 21% (ranging from 10 to 33%), and 40% of them reported persistently high PTSD symptoms 3 years after post exposure. PTSD symptoms were also significantly higher among exposed healthcare workers (HCWs) than unexposed control group, particularly among allied HCWs, followed by nurses and physicians…

The importance of providing mental health service to people affected by the epidemic of infectious diseases are highly recognized by the academic society and the general public. In 2007, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) announced Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings [8], which has been widely adapted to direct mental health service after disasters, including infectious disease epidemics. The IASC guidelines are organized around a 4-tiered intervention pyramid: (1) restoring basic services and security for the affected population, (2) strengthening family and community networks, (3) providing distressed individuals with psychosocial support, and (4) providing specialized mental health intervention for severely affected survivors. Other strategies or models of intervention have also been practiced in various of settings [9]. However, systematic and well-designed intervention studies targeted at the prevention of PTSD after disasters are unavailable until now.

With considerations of the already large and will still increasing number of people exposed to the current COVID-19, we believe it urgent to provide mental health service targeted at prevention of PTSD to survivors and other people exposed to COVID-19. Possible strategies include, but not limited to health education, psychosocial support and counselling service to the general population, as well as early intervention, including psychosocial support, psychotherapies, and pharmacological treatments to vulnerable and high-risk groups. ”

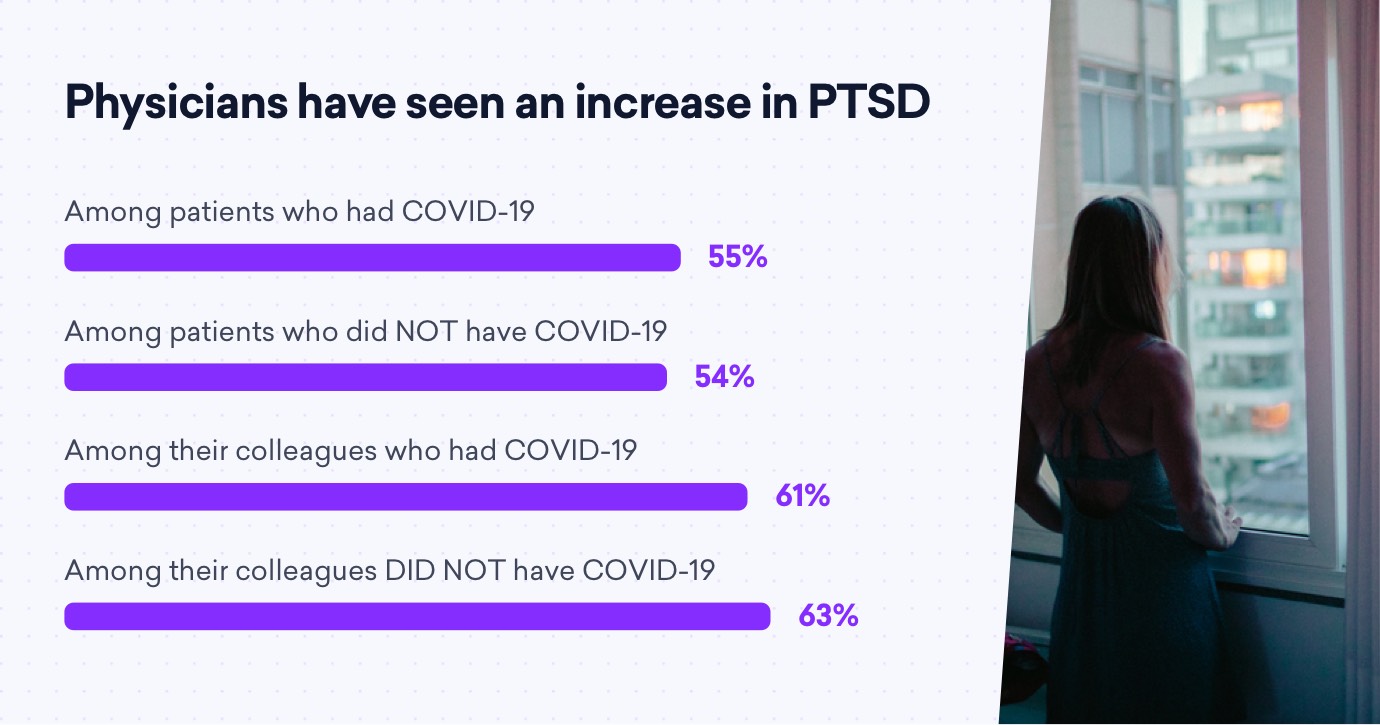

In a recent poll of global Sermo physicians, 60% report having seen an increase of PTSD symptoms among their healthcare colleagues who had COVID-19; and 63% have seen an increase of PTSD symptoms among colleagues who DID NOT have COVID-19. Seventy-four percent of physicians feel there is greater need for early intervention and prevention of PTSD post-COVID.

In another poll, 55% of physicians report seeing an increase of PTSD symptoms among their patients who had COVID-19; and 54% are seeing an increase of PTSD symptoms among patients who did not have COVID-19.

Regarding the alarming trend of mass shootings that have skyrocketed this year in the U.S., many health experts question whether post-traumatic stress triggered by the global pandemic could be connected to the rising gun violence. And 46% of Sermo physicians agree that this violence could be linked to the increased mental health issues and PTSD symptoms that are emerging from COVID-19.

Here is more of what Sermo physicians have to say on this topic:

In any downturn; Lack of employment and economic issues are mostly related to PTSD than Pandemic itself. Economic depression with housing market collapse about 10 to 12 years ago probably caused the same kind of mental status, present pandemic may be indirectly responsible for decreased employment.

Cardiology

Absolutely!

I have observed the ppl have been more aggressive, rude and pugnacious in public, especially on the roads!

The isolation has lead to an increase of solipsism in our community.

Orthopedic Surgery

Speaking as a trauma therapist, it is worth reflecting on causality. People are not “catching” an illness like COVID. Our mental (and physical health) are intricately woven into the world and people around us. I have a feeling that – when we look back at this time from ten or twenty years in the future – we will recognize that we didn’t focus enough on our collective well-being. We allowed a lot of people to be left behind emotionally and mass shootings are perhaps one of the more visible reminders of that.

General Practice (GP)

Mass shootings were a huge problem even before the current pandemic. Having said that, the pandemic is a risk factor for a lot of mental health pathologies for sure.

General Practice (GP)